THE CHEMICALS BEHIND ADDICTION

There

are four main chemicals your body produces that help you feel good: Dopamine,

Norepinephrine, Oxytocin, and Serotonin.

When you’re out doing certain activities [includes skydiving, white water kayaking, riding a rollercoaster, etc.], your brain releases these chemicals to give you a rush, or make you bond with people or remember the details of a moment.

While the chemicals are busy helping you feel good, your body and mind are linking that feeling to what you’re doing. Basically, it’s these chemicals, and the associations they reflect, that keep you coming back for more. Now that’s cool when the experiences are good things like adventures, or hobbies, or healthy sex, but when the experience is viewing pornography, the end result can get pretty ugly.

DOPAMINE

First up is Dopamine. Dopamine does a lot of things from helping you focus and learn to helping you control the movement of your body. But it usually is talked about as a pleasure chemical. Dopamine engages the reward-learning systems in the brain, so it’s also a kind of learning chemical. When you’re doing something cool, it rewards you with feelings of excitement, pleasure, and arousal, while simultaneously “taking notes” on what’s happening, so you can remember how to do it again.

Healthy Sex:

This chemical is awesome in a relationship! When you have sex with someone you care about, Dopamine kicks in to help you focus on them, and you develop a healthier relationship.

Pornography:

When you use an image to trigger the release of Dopamine, there isn’t an actual person involved for you to focus on, so you end up focusing on the sex act and sex organs. You learn to look at others as objects and forget about their personality, talents, quirks, etc. Porn also releases exaggerated levels of dopamine, possibly due to the longer anticipatory stage and increased novelty. This means more fuel. And what’s more it impedes the release of prolactin, which is a “braking” chemical that helps you feel full or done. [More on Prolactin below] A lot of fuel and no brakes sounds like a problem.

NOREPINEPRHINE

This chemical may sound like the name of a new metal band (hey, that’s actually not a bad idea), but it’s really what gives you an adrenaline rush and makes your heart pound. The details of whatever you’re doing when this chemical is released are seared into your brain so you easily remember them later. They help make you hyper-aware of novelty and increase your general awareness as well.

Healthy Sex:

Simply put, Norepinephrine makes sex exciting. When you’re having sex, it’s this chemical that makes your heart beat faster and creates a lasting memory of your time with that person.

Pornography:

When you use porn, Norepinephrine is released, making the images hard to forget. When you remember the image and the experience, there’s no personal connection, which can make you feel lonely and even worthless. The strong memories also make it hard to stay away from pornography, which can make for a vicious cycle.

OXYTOCIN

This chemical helps connect you to your family. In fact, it’s what creates the bond between a mom and a newborn baby. The craziest thing is that Oxytocin helps people fall in love. (But don’t bother trying to put it in a potion or a bottle or anything—it doesn’t work. I’m not going to tell you how I know, I just know.) Oxytocin is released when people hold hands, embrace, and kiss. It is correlated with trust and decreases in anxiety. But it isn’t just about love, it’s about tuning us into social information so we can analyze it more appropriately.

Healthy Sex:

When you have sex, kiss, cuddle, hold hands, etc., Oxytocin is released, making the bond between you stronger. When you have sex, a tidal wave of Oxytocin is released at climax. This helps you relax and creates an emotional bond between you and your partner as your fear decreases and your trust increases.

Pornography:

When your “relationship” is being carried on with an image, there’s not as much social information to take in, but some oxytocin is still released at orgasm. The momentary feelings of contentment and calmness brought on by oxytocin can lead you back to pornography when you need an emotional connection or to relieve stress. The problem is that an image will never fill your need for a relationship. Real people hit all of the oxytocin “hot buttons.”

PROLACTIN

Prolactin does a lot of things. The root of the word is to encourage lactation, but it has a range of other effects from affecting hair growth to promoting brain development. In sexual process it surges after orgasm and acts to inhibit dopamine in order to bring about feelings of satiety, or feeling done, just like with feeling full after a large meal.

Healthy Sex:

After sex with a partner, prolactin is released in large amounts to bring the act to an end and begin a period of rest and satiety. Along with oxytocin, it enhances the sense of togetherness with another person.

Pornography:

Prolactin released after a heterosexual activity is 4 times higher than the amount released after self-stimulation to pornography. This means that real sex makes you feel 4 times more satisfied than pornography does. If you’re getting more dopamine and less prolactin than usual, you can see how pornography can quickly become repetitive and difficult to control.

SEROTONIN

Last up is the calming chemical. A lot of times people call Serotonin the “natural Prozac” because it helps you feel happy, calm, satisfied, and relieved of stress. Like prolactin, serotonin is generally inhibitory to dopamine and is released to signal the end of a sexual act.

Healthy Sex:

Following sexual climax with a partner, the release of Serotonin relaxes you and makes you feel satisfied. You attribute those good feelings with your partner and you remember and associate that feeling with them.

Pornography:

When you regularly view porn, you may begin using it to self-medicate when you’re feeling blue, or to escape the trials and pressures of life. A lot of porn users can’t even fall asleep unless they’ve had their porn fix, because the release of Serotonin helps them relax and sleep. That’s why pornography becomes a lot of people’s “drug of choice.”

?

When it comes down to it, this natural chemical stuff is pretty cool. The coolest part is that there are lots of awesome ways, including sex, that your brain releases these chemicals that make you feel great. And when you choose to avoid pornography, you choose to avoid all of the negative feelings, emotions, and hassles that come with it. That leaves you free to live your life and experience it on your terms, without letting addiction hold you back.

For more, check out "The Brain and Addiction", and "Tolerance: Porn becomes the Norm".

When you’re out doing certain activities [includes skydiving, white water kayaking, riding a rollercoaster, etc.], your brain releases these chemicals to give you a rush, or make you bond with people or remember the details of a moment.

While the chemicals are busy helping you feel good, your body and mind are linking that feeling to what you’re doing. Basically, it’s these chemicals, and the associations they reflect, that keep you coming back for more. Now that’s cool when the experiences are good things like adventures, or hobbies, or healthy sex, but when the experience is viewing pornography, the end result can get pretty ugly.

DOPAMINE

First up is Dopamine. Dopamine does a lot of things from helping you focus and learn to helping you control the movement of your body. But it usually is talked about as a pleasure chemical. Dopamine engages the reward-learning systems in the brain, so it’s also a kind of learning chemical. When you’re doing something cool, it rewards you with feelings of excitement, pleasure, and arousal, while simultaneously “taking notes” on what’s happening, so you can remember how to do it again.

Healthy Sex:

This chemical is awesome in a relationship! When you have sex with someone you care about, Dopamine kicks in to help you focus on them, and you develop a healthier relationship.

Pornography:

When you use an image to trigger the release of Dopamine, there isn’t an actual person involved for you to focus on, so you end up focusing on the sex act and sex organs. You learn to look at others as objects and forget about their personality, talents, quirks, etc. Porn also releases exaggerated levels of dopamine, possibly due to the longer anticipatory stage and increased novelty. This means more fuel. And what’s more it impedes the release of prolactin, which is a “braking” chemical that helps you feel full or done. [More on Prolactin below] A lot of fuel and no brakes sounds like a problem.

NOREPINEPRHINE

This chemical may sound like the name of a new metal band (hey, that’s actually not a bad idea), but it’s really what gives you an adrenaline rush and makes your heart pound. The details of whatever you’re doing when this chemical is released are seared into your brain so you easily remember them later. They help make you hyper-aware of novelty and increase your general awareness as well.

Healthy Sex:

Simply put, Norepinephrine makes sex exciting. When you’re having sex, it’s this chemical that makes your heart beat faster and creates a lasting memory of your time with that person.

Pornography:

When you use porn, Norepinephrine is released, making the images hard to forget. When you remember the image and the experience, there’s no personal connection, which can make you feel lonely and even worthless. The strong memories also make it hard to stay away from pornography, which can make for a vicious cycle.

OXYTOCIN

This chemical helps connect you to your family. In fact, it’s what creates the bond between a mom and a newborn baby. The craziest thing is that Oxytocin helps people fall in love. (But don’t bother trying to put it in a potion or a bottle or anything—it doesn’t work. I’m not going to tell you how I know, I just know.) Oxytocin is released when people hold hands, embrace, and kiss. It is correlated with trust and decreases in anxiety. But it isn’t just about love, it’s about tuning us into social information so we can analyze it more appropriately.

Healthy Sex:

When you have sex, kiss, cuddle, hold hands, etc., Oxytocin is released, making the bond between you stronger. When you have sex, a tidal wave of Oxytocin is released at climax. This helps you relax and creates an emotional bond between you and your partner as your fear decreases and your trust increases.

Pornography:

When your “relationship” is being carried on with an image, there’s not as much social information to take in, but some oxytocin is still released at orgasm. The momentary feelings of contentment and calmness brought on by oxytocin can lead you back to pornography when you need an emotional connection or to relieve stress. The problem is that an image will never fill your need for a relationship. Real people hit all of the oxytocin “hot buttons.”

PROLACTIN

Prolactin does a lot of things. The root of the word is to encourage lactation, but it has a range of other effects from affecting hair growth to promoting brain development. In sexual process it surges after orgasm and acts to inhibit dopamine in order to bring about feelings of satiety, or feeling done, just like with feeling full after a large meal.

Healthy Sex:

After sex with a partner, prolactin is released in large amounts to bring the act to an end and begin a period of rest and satiety. Along with oxytocin, it enhances the sense of togetherness with another person.

Pornography:

Prolactin released after a heterosexual activity is 4 times higher than the amount released after self-stimulation to pornography. This means that real sex makes you feel 4 times more satisfied than pornography does. If you’re getting more dopamine and less prolactin than usual, you can see how pornography can quickly become repetitive and difficult to control.

SEROTONIN

Last up is the calming chemical. A lot of times people call Serotonin the “natural Prozac” because it helps you feel happy, calm, satisfied, and relieved of stress. Like prolactin, serotonin is generally inhibitory to dopamine and is released to signal the end of a sexual act.

Healthy Sex:

Following sexual climax with a partner, the release of Serotonin relaxes you and makes you feel satisfied. You attribute those good feelings with your partner and you remember and associate that feeling with them.

Pornography:

When you regularly view porn, you may begin using it to self-medicate when you’re feeling blue, or to escape the trials and pressures of life. A lot of porn users can’t even fall asleep unless they’ve had their porn fix, because the release of Serotonin helps them relax and sleep. That’s why pornography becomes a lot of people’s “drug of choice.”

?

When it comes down to it, this natural chemical stuff is pretty cool. The coolest part is that there are lots of awesome ways, including sex, that your brain releases these chemicals that make you feel great. And when you choose to avoid pornography, you choose to avoid all of the negative feelings, emotions, and hassles that come with it. That leaves you free to live your life and experience it on your terms, without letting addiction hold you back.

For more, check out "The Brain and Addiction", and "Tolerance: Porn becomes the Norm".

How addiction hijacks the brain

Desire initiates the process, but learning sustains it.

The word "addiction" is derived from a Latin term for "enslaved by" or "bound to." Anyone who has struggled to overcome an addiction — or has tried to help someone else to do so — understands why.

Addiction exerts a long and powerful influence on the brain that manifests in three distinct ways: craving for the object of addiction, loss of control over its use, and continuing involvement with it despite adverse consequences. While overcoming addiction is possible, the process is often long, slow, and complicated. It took years for researchers and policymakers to arrive at this understanding.

In the 1930s, when researchers first began to investigate what caused addictive behavior, they believed that people who developed addictions were somehow morally flawed or lacking in willpower. Overcoming addiction, they thought, involved punishing miscreants or, alternately, encouraging them to muster the will to break a habit.

The scientific consensus has changed since then. Today we recognize addiction as a chronic disease that changes both brain structure and function. Just as cardiovascular disease damages the heart and diabetes impairs the pancreas, addiction hijacks the brain. Recovery from addiction involves willpower, certainly, but it is not enough to "just say no" — as the 1980s slogan suggested. Instead, people typically use multiple strategies — including psychotherapy, medication, and self-care — as they try to break the grip of an addiction.

Another shift in thinking about addiction has occurred as well. For many years, experts believed that only alcohol and powerful drugs could cause addiction. Neuroimaging technologies and more recent research, however, have shown that certain pleasurable activities, such as gambling, shopping, and sex, can also co-opt the brain. Although the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) describes multiple addictions, each tied to a specific substance or activity, consensus is emerging that these may represent multiple expressions of a common underlying brain process.

From liking to wanting

Nobody starts out intending to develop an addiction, but many people get caught in its snare. According to the latest government statistics, nearly 23 million Americans — almost one in 10 — are addicted to alcohol or other drugs. More than two-thirds of people with addiction abuse alcohol. The top three drugs causing addiction are marijuana, opioid (narcotic) pain relievers, and cocaine.

Genetic vulnerability contributes to the risk of developing an addiction. Twin and adoption studies show that about 40% to 60% of susceptibility to addiction is hereditary. But behavior plays a key role, especially when it comes to reinforcing a habit.

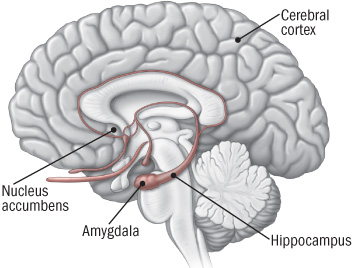

Pleasure principle. The brain registers all pleasures in the same way, whether they originate with a psychoactive drug, a monetary reward, a sexual encounter, or a satisfying meal. In the brain, pleasure has a distinct signature: the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, a cluster of nerve cells lying underneath the cerebral cortex (see illustration). Dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens is so consistently tied with pleasure that neuroscientists refer to the region as the brain's pleasure center.

The brain's reward center

Addictive drugs provide a shortcut to the brain's reward system by flooding the nucleus accumbens with dopamine. The hippocampus lays down memories of this rapid sense of satisfaction, and the amygdala creates a conditioned response to certain stimuli.

|

All drugs of abuse, from nicotine to heroin, cause a particularly powerful surge of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens. The likelihood that the use of a drug or participation in a rewarding activity will lead to addiction is directly linked to the speed with which it promotes dopamine release, the intensity of that release, and the reliability of that release. Even taking the same drug through different methods of administration can influence how likely it is to lead to addiction. Smoking a drug or injecting it intravenously, as opposed to swallowing it as a pill, for example, generally produces a faster, stronger dopamine signal and is more likely to lead to drug misuse.

Learning process. Scientists once believed that the experience of pleasure alone was enough to prompt people to continue seeking an addictive substance or activity. But more recent research suggests that the situation is more complicated. Dopamine not only contributes to the experience of pleasure, but also plays a role in learning and memory — two key elements in the transition from liking something to becoming addicted to it.

According to the current theory about addiction, dopamine interacts with another neurotransmitter, glutamate, to take over the brain's system of reward-related learning. This system has an important role in sustaining life because it links activities needed for human survival (such as eating and sex) with pleasure and reward. The reward circuit in the brain includes areas involved with motivation and memory as well as with pleasure. Addictive substances and behaviors stimulate the same circuit — and then overload it.

Repeated exposure to an addictive substance or behavior causes nerve cells in the nucleus accumbens and the prefrontal cortex (the area of the brain involved in planning and executing tasks) to communicate in a way that couples liking something with wanting it, in turn driving us to go after it. That is, this process motivates us to take action to seek out the source of pleasure.

Tolerance and compulsion. Over time, the brain adapts in a way that actually makes the sought-after substance or activity less pleasurable.

In nature, rewards usually come only with time and effort. Addictive drugs and behaviors provide a shortcut, flooding the brain with dopamine and other neurotransmitters. Our brains do not have an easy way to withstand the onslaught.

Addictive drugs, for example, can release two to 10 times the amount of dopamine that natural rewards do, and they do it more quickly and more reliably. In a person who becomes addicted, brain receptors become overwhelmed. The brain responds by producing less dopamine or eliminating dopamine receptors — an adaptation similar to turning the volume down on a loudspeaker when noise becomes too loud.

As a result of these adaptations, dopamine has less impact on the brain's reward center. People who develop an addiction typically find that, in time, the desired substance no longer gives them as much pleasure. They have to take more of it to obtain the same dopamine "high" because their brains have adapted — an effect known as tolerance.

At this point, compulsion takes over. The pleasure associated with an addictive drug or behavior subsides — and yet the memory of the desired effect and the need to recreate it (the wanting) persists. It's as though the normal machinery of motivation is no longer functioning.

The learning process mentioned earlier also comes into play. The hippocampus and the amygdala store information about environmental cues associated with the desired substance, so that it can be located again. These memories help create a conditioned response — intense craving — whenever the person encounters those environmental cues.

Cravings contribute not only to addiction but to relapse after a hard-won sobriety. A person addicted to heroin may be in danger of relapse when he sees a hypodermic needle, for example, while another person might start to drink again after seeing a bottle of whiskey. Conditioned learning helps explain why people who develop an addiction risk relapse even after years of abstinence.

Resources

National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug InformationP.O. Box 2345

Rockville, MD 20847 800-729-6686 (toll-free) http://ncadi.samhsa.gov

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism5635 Fishers Lane, MSC 9304

Bethesda, MD 20892 301-443-3860 www.niaaa.nih.gov

National Institute on Drug Abuse6001 Executive Blvd., Room 5213

Bethesda, MD 20892 301-443-1124 www.nida.nih.gov

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration1 Choke Cherry Road

Rockville, MD 20857 877-276-4727 (toll-free) www.samhsa.gov |

The long road to recovery

Because addiction is learned and stored in the brain as memory, recovery is a slow and hesitant process in which the influence of those memories diminishes.

About 40% to 60% of people with a drug addiction experience at least one relapse after an initial recovery. While this may seem discouraging, the relapse rate is similar to that in other chronic diseases, such as high blood pressure and asthma, where 50% to 70% of people each year experience a recurrence of symptoms significant enough to require medical intervention.

Fortunately a number of effective treatments exist for addiction, usually combining self-help strategies, psychotherapy, and rehabilitation. For some types of addictions, medication may also help.

The precise plan varies based on the nature of the addiction, but all treatments are aimed at helping people to unlearn their addictions while adopting healthier coping strategies — truly a brain-based recovery program.

Benowitz NL. "Nicotine Addiction," The New England Journal of Medicine (June 17, 2010): Vol. 362, No. 24, pp. 2295–303.

Brady KT, et al., eds. Women and Addiction: A Comprehensive Handbook (The Guilford Press, 2009).

Chandler RK, et al. "Treating Drug Abuse and Addiction in the Criminal Justice System: Improving Public Health and Safety," Journal of the American Medical Association (Jan. 14, 2009): Vol. 301, No. 2, pp. 183–90.

Greenfield SF, et al. "Substance Abuse Treatment Entry, Retention, and Outcome in Women: A Review of the Literature," Drug and Alcohol Dependence (Jan. 5, 2007): Vol. 86, No. 1, pp. 1–21.

Koob GF, et al. "Neurocircuitry of Addiction," Neuropsychopharmacology (Jan. 2010): Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 217–38.

McLellan AT, et al. "Drug Dependence, A Chronic Medical Illness: Implications for Treatment, Insurance, and Outcomes Evaluation," Journal of the American Medical Association (Oct. 4, 2000): Vol. 284, No. 13, pp. 1689–95.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction(National Institutes of Health, Aug. 2010).

Polosa R, et al. "Treatment of Nicotine Addiction: Present Therapeutic Options and Pipeline Developments," Trends in Pharmacological Sciences (Jan. 20, 2011): E-publication.

Potenza MN, et al. "Neuroscience of Behavioral and Pharmacological Treatments for Addictions," Neuron (Feb. 24, 2011): Vol. 69, No. 4, pp. 695–712.

Shaffer HJ, et al. "Toward a Syndrome Model of Addiction: Multiple Expressions, Common Etiology," Harvard Review of Psychiatry (Nov.–Dec. 2004): Vol. 12, No. 6, pp. 367–74. *

Stead LF, et al. "Nicotine Replacement Therapy for Smoking Cessation," Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Jan. 23, 2008): Doc. No. CD000146.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use & Health, 2009.

For more references, please see www.health.harvard.edu/mentalextra.

No comments:

Post a Comment